The Evolution of Telemedicine

The clinical progression of telemedicine from the early 2000's to present

A note from Robert

Hey, thanks for signing up for HealthTech Happy Hour. I have been researching and writing about telehealth, virtual care, digital health, value-based care, and ETC for a while and it is always exciting to see signups from people who share these interests or want to engage in the discussion. In the past week, >550 people have read Health Tech Happy Hour—thanks for being one of them. Ultimately, I hope you can take something away from this that allows you to make an impact on patients that rely on our healthcare system every day.

Setting the Stage: Digital Health, Telemedicine, and Virtual Care

It all started in the early 2000s when internet and internet use started to grow exponentially. In 2007, the iPhone emerged. After that, the ability of the global population to access products and services via the internet through mobile networks fundamentally changed our society, our culture, and the market for healthcare services.

Since the early 2000s, the use of the internet and the advent of smartphones have ushered in a new world that has been rapidly evolving over the past 15 years (see the charts below).

Figure 1: % of US Adults Who Say They Use the Internet, by Age

Figure 2: % of US Adults Who Say they Own a Smartphone or Cellphone

Take a look at the research behind these charts at PEW Research.

Early Telemedicine

Telemedicine began with the concept that a physician could deliver consultations with a patient via audio-only telephone or audio-visual communications tools over the internet. Naturally, the primary benefit of this is improved access to and experience of care. In rural areas, telemedicine allows specialists and primary care teams to provide access to patients who lack geographic proximity to a brick-and-mortar clinic.

The primary criticisms of telemedicine are based on the scope of practice. There truly are certain diagnoses, procedures, and patients that benefit from in-person services. Conversely, there are some conditions and patients where telemedicine is inappropriate or even dangerous. Advocates of telemedicine, or the broader term telehealth, are often too enthusiastic about the ability of telemedicine to “take over the world.” Teladoc and Amwell, in their original business models, took care of mostly sinus infections, rashes, and other low severity, acute needs that have a simple diagnosis and mostly require a straightforward prescription (see Figure 3). Simply put, patients cannot receive a lumbar puncture via telemedicine, and conditions like diabetes require long-term care and monitoring from the same physician.

Figure 3: Teladoc’s conditions advertised on their website

For low-severity, frequent, and acute conditions, telemedicine, in its earliest form, provides convenient access for patients that require a simple fix, but this is hardly a transformative concept. In this form, telemedicine functions largely as a consumer product rather than a bombastic healthcare innovation.

This characterization is also exposed by the more recent digital health darlings Ro and Hims & Hers who took this concept a step further. Both of these businesses (or, pill mills, if you prefer) have improved on the original Teladoc model by making it even easier for consumers to obtain certain low-risk prescription medications over the internet. Both companies began in erectile dysfunction, hair loss, and skincare products that require a prescription but are generally low-risk. In this case, the companies function with a carefully crafted consumer brand, aggressive D2C marketing, and the goal of high-margin subscription revenue on the products. Again, these are really consumer product companies.

I mean no harsh criticism of these companies as they serve a need for more convenient healthcare experiences—even if they are not moving the needle on our critical health situation in the United States. Quite honestly, even I went running to Ro when I noticed the first signs of potential balding on my head. Instead of paying $500 for a dermatologist visit, Ro allowed me to quickly jump online and obtain the medications required to get ahead of male patterned baldness. The outcome had I visited a dermatologist would have been the same.

Telemedicine, whether the live audio-visual of Teladoc or the store-and-forward version of companies like Ro, Hims & Hers, and Nurx, does provide significant benefit for patients looking to access a limited set of services. But, again, the playbook for these companies is not of healthcare strategy but that of online consumer products with a healthcare regulatory twist.

Population Health in the US

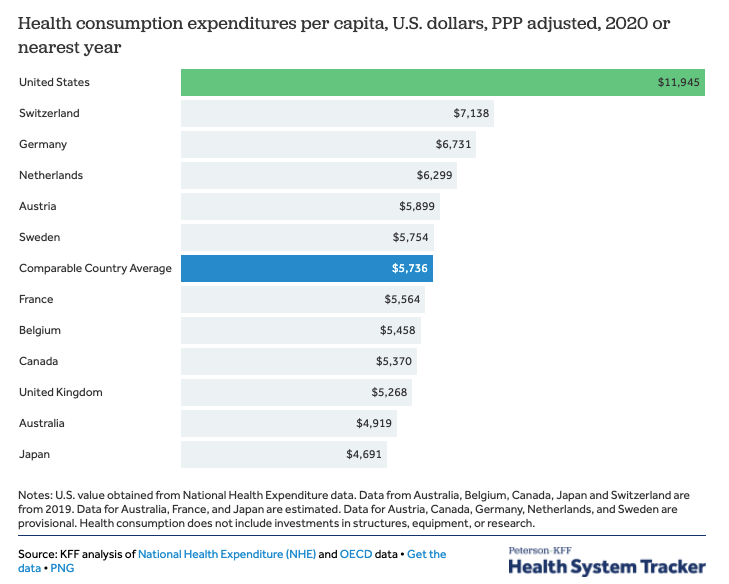

Taking a step back and putting on my health policy hat, the US is in rather dire straights with respect to our per capita healthcare expenditures. Healthcare debt is the #1 reason for bankruptcy in the US. People delay or avoid needed healthcare services due to cost leading to even more suffering and expense down the road.

This point has been harked on for many years, but the gap continues to widen and the problems continue to grow. The US spends more on healthcare, receives comparably worse population health outcomes, and bankrupts more citizens than any comparable country.

The spending is attributable and illustrated well by the chart, below. Most of the US spending in 2014 (i.e., these things do not get updated very frequently), is attributable to our chronic disease epidemic—particularly cardiovascular and cardiometabolic diseases—for which prevention is a particularly well-known, but a poorly executed intervention. Thus, in the next decade “the money” for telemedicine companies will go to those companies that successfully develop virtual chronic disease programs that 1. prove outcomes, 2. attract patients, and 3. retain patients for the long-term.

See more about these charts in the excellent RAND Corporation report.

Covid-19 Impact on Telehealth-First Businesses

Traditional telemedicine companies like Teladoc have made moves in the past two years to shift business from low-severity, acute needs to chronic care. Teladoc’s acquisition of Livongo (i.e., Livongo has a virtual program for hypertension and diabetes) is a clear illustration of this strategy. During early Covid-19, practices shut down and patients with diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, cancers, and other conditions were forced to either receive no care or access care via telemedicine technologies. Teladoc was wagering on this trend both accelerating and maintaining in the decade ahead—you can tell they thought this based on their massive Livongo valuation that far outpaced Livongo’s revenue. Covid-19, to many, was a boom and bust event for telemedicine, telehealth, and virtual care businesses. But was it?

There was a boom-bust-bubble-like feel to Covid-19’s impact on telemedicine companies, but it has set the stage for significant growth over the next decade.

A few key thoughts:

Patients who never otherwise would have accessed telemedicine services were introduced—thus, accelerating the potential market size over the next 10 years.

Millennials and Gen Z-ers are very comfortable with telemedicine and Covid-19 allowed them to access it in a wide variety of ways for a variety of conditions. As they age, they will acquire chronic conditions. They will expect virtual experiences of care.

Mental health impacts from Covid-19 and the poor distribution of practitioners lend themselves well to the boom of virtual mental health companies. This market will continue to grow and models that work will win.

Telehealth has wide-bipartisan support in congress and every single house member and senator is aware of it now, due to Covid-19.

Medicare has already indicated a state of permanence of telehealth services.

Commercial payors, who are traditionally skeptical, have attained a new level of comfort with telehealth network providers.

Mail-order and delivery pharmacies have accelerated the complimentary good of telehealth because “why not do everything virtually?”

But, the most important impact of Covid-19 on our telemedicine-first providers is a new competition.

The pandemic forced every brick-and-mortar health system and single provider practice to implement their telehealth plans early. Physicians were forced to take visits virtually despite years of resistance. At this point, nearly every patient’s physician was offering some form of virtual appointment.

For Teladoc, Amwell, MDLive, and the other companies, this was a death sentence to their prior business models. Their only competitive moat in the market was that they were the only ones offering audio-visual technology for appointments with a physician. Now, across the country, patients could receive the same convenience from their trusted, long-time physician. This was the nail in the coffin for the low-severity, acute telemedicine business model. The brick-and-mortar clinics entered the telemedicine market.

Thus, Covid-19 forced Teladoc, Amwell, MDLive, and the like on a quest to find new chronic care or specialty business models.

Telemedicine meets Remote-Patient Monitoring (RPM)

When Teladoc acquired Livongo, it was like that whole Mayan Calendar 2012 prophecy (remember that?). The RPM crowd has been talking about the use of IoT devices to monitor patients in the home for both acute and chronic conditions for about a decade and a half. Naturally, they saw a future where telemedicine companies could shift their care models to chronic care via the use of connected devices. But, it was not until 2018-2019 that Medicare began paying for remote-physiological monitoring services—thus creating a billion-dollar market overnight.

With this in mind, Teladoc finally fulfilled the prophecy, but, like the doomsday that never came in 2012, it was not as rapid and revolutionary as foreseen. The issue, for Teladoc/Livongo, still resides in the impact that the brick-and-mortar clinics had on the market. Long-term clinical relationships matter for patient populations with the highest rates of chronic conditions, and specifically, the highest prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. Patients on Medicare and age 50+ have often been with the same practice for years and switching to a newfangled virtual primary care clinic was not in the cards when it is possible to receive the same services from your trusty Primary Care Associates, P.C.

During early Covid-19 and after record RPM investment, brick-and-mortar clinics were inundated by remote-patient monitoring technology companies looking to help them adopt the IoT approach to chronic care and take advantage of Medicare’s reimbursement. So, not only did Primary Care Associates, P.C. adopt an audio-visual telemedicine technology early in the pandemic, but they also started signing up for RPM platforms—just like Teladoc/Livongo.

It is important to note that RPM-based chronic care models are effective for a number of conditions when operated correctly and meaningfully (see this report from AHRQ. I am a firm believer that these care models will become the standard of care in 5 years or less as the evidence continues to mount (but, there are a lot of bad programs).

In the early stages of telemedicine, it was about improved access. Now, telemedicine has expanded to the concept of virtual care that can be more about enhanced care models that cannot be delivered via traditional episodic care approaches. Virta Health has successfully proved that its virtual care model can reverse type 2 diabetes. We have entered a new world that is no longer about telemedicine adoption and volume-driven care, but the development of new, intensive, technology-driven, longitudinal care models. As someone who operates an RPM program for diabetes, hypertension, and congestive heart failure, I see the positive impact the data and the program have on patients, providers, and the nurses operating the RPM program. Anecdotally, these things are great.

So, what will the future look like?

Teladoc and Amwell, and similar, have begun looking into how to become virtual primary care clinics complete with RPM for chronic conditions, mail-order labs, and audio-visual visits. They may open brick-and-mortar locations or co-located spaces in employer offices.

Teladoc and Amwell, and similar, have begun building and implementing enterprise software to allow them to be the telemedicine operating system for large health systems in terms of both technology and physician staffing—a key issue for hospitals (see my previous article). This is the key strategy as it leverages the decades of trust-building marketing performed by health systems and helps health systems maintain in-system referrals.

Teladoc and Amwell, and similar, will seek to target self-insured employers to offer services as a benefit at a lower cost than the typical ASO insurance network—these clinical models will look like #1.

Highly-technical virtual specialty care companies will segment the market and seek to drive better outcomes via structured evidence-based clinical models for specific patient populations or conditions. (See Folx Health, Tia, Virta Health, Parsley Health). These organizations will partner with brick-and-mortar health systems and offer stand-alone virtual services. Segmentation has heretofore not occurred in healthcare aside from physician specialty—it matters.

Academic medical centers will launch national, virtual centers of excellence relying on their national prestige (see Circle Health and UCSF) to attract patients. They will either partner or build it themselves—partnering has dominated the field thus far.

Most brick-and-mortar primary care clinics will adopt RPM-based care models after specialty societies declare them as the standard of care.

Labs, procedures, and care that requires “the laying of the hands” will continue to be offered in-person—blood draws really cannot be done at home. Thus, this single point of advantage will favor the brick-and-mortar clinics especially as they adopt the same technologies as the virtual-care first companies. Many labs will become mail-order—especially as we enter the coming genetic testing revolution (cheek swab or saliva). Stand-alone, virtual first companies, aside from the cases above, will need a B2B2C strategy in place.

These are a few of the current trends in the market to expect in the coming decade. The acceleration of internet technology and smartphones has opened a new world in which we can reimagine the delivery of healthcare. Improved access, more personalized care, better experiences, and enhanced outcomes can be expected from many of these models. However, there will be cases in which the size of the market leads to bad behavior—see Cerebral. Congress has indicated a willingness to reduce some of the barriers to these care models and a wide, bi-partisan acceptance of telehealth.

Despite all the advances, it is important to remember that too much healthcare can often be as detrimental as not enough. It is all about delivering the right care, to the right patient, at the right time, but more importantly, the best healthcare is prevention—improving diet, exercise, and other lifestyle factors.

Reading this from the web? Interested in learning more?