The Growing Crisis of Homelessness and How Medicaid Innovations May Help

How states use the Section 1115 Waiver and technology platforms to build effective programs

A record-high 653,104 people experienced homelessness on a single night in January 2023. This is more than a 12.1 percent increase over the previous year.

Homelessness represents one of America's most pressing public health and social challenges. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) US Annual Homelessness Assessment Report, between October 2020 and September 2021, 1.2 million individuals experienced sheltered homelessness. This report does not contain the numbers of those experiencing unsheltered homelessness due to challenges counting during the peak COVID-19 pandemic years. The report estimates that of all people experiencing homelessness, adult-only households accounted for 67% while families with children accounted for 31%. Many more individuals and families face housing instability where future homelessness is just one step or one eviction away.

A report by the National Alliance to End Homelessness suggests the crisis has intensified in recent years, with unsheltered homelessness rising dramatically from 20% of the total homeless population before the COVID-19 pandemic to nearly 40% in 2023.

More People Than Ever Are Experiencing Homelessness for the first time. From 2019-2023, the number of people who entered emergency shelter for the first time increased more than 23 percent.

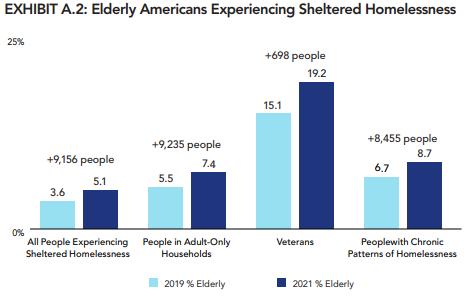

Homelessness also affects older adults. Exhibit A.2. from the HUD report shows the growth in older adult (or, elderly) populations experiencing sheltered homelessness from 2019 to 2021. Of particular note is the high rate of veteran homelessness.

This is important to note as it has recently popped up in the 2024 presidential campaign rhetoric. Now president-elect Trump has made it clear his desire to end veteran homelessness, see here. The extent to which this will occur will be critical to watch as previous attempts in the first Trump Administration did not produce the desired outcomes.

Homelessness, Housing Instability, and the Intersection with Health Care Services

The human toll of homelessness extends far beyond the immediate trauma of housing instability or lack of housing. People experiencing homelessness face significantly higher rates of acute and chronic health conditions, mental illness, and substance use disorders. These health challenges, combined with obvious financial, transportation, and other barriers to accessing regular preventive care, result in more frequent emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Studies have shown that individuals experiencing homelessness are among the highest utilizers of costly emergency health care services, creating substantial expenses for both government health care programs and hospitals in the form of uncompensated care.

The Role of Medicaid

This intersection of homelessness and health care costs has led policymakers to explore how health care funding and delivery systems might be leveraged to address housing instability and homelessness. Medicaid, the federal-state partnership that provides health coverage to low-income Americans, is the primary area in which this work is occurring.

Medicaid is the nation's primary public health insurance program for low-income Americans, jointly funded by federal and state governments but administered at the state level. While the federal government establishes core requirements for eligibility and covered services, states have significant flexibility in designing and operating their Medicaid programs, leading to considerable variation across the country in terms of who qualifies and what services are covered. This variation, however, also allows for innovation where individual states can test certain policies and then others can adopt if they prove successful.

The federal government typically covers between 50% and 83% of each state's Medicaid costs through a matching formula (FMAP) based on the state's per capita income, with poorer states receiving a higher federal match. Currently, Medicaid provides health coverage to approximately 80 million Americans, making it the nation's largest health insurer and a crucial component of the health care safety net. As the primary source of health insurance for many people experiencing homelessness, Medicaid offers both the infrastructure and financial resources that could support innovative housing solutions.

Medicaid and the use of the Section 1115 Waiver to Innovate

Section 1115 of the Social Security Act provides states with a powerful tool for such innovation. These "1115 waivers" allow states to waive certain federal Medicaid requirements or limitations in order to test new approaches to delivering and paying for care, provided these experiments promote the objectives of the Medicaid program. Typically these waivers, and the programs described within them, require a reasonable hypothesis that the outcomes will result in better health at lower cost. The waiver process requires states to submit detailed proposals to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) demonstrating how their innovative approach will improve care while maintaining budget neutrality.

The 1115 Waiver and Programs to Address Homelessness

States have increasingly turned to 1115 waivers as a mechanism to address homelessness. A recent paper by Willison and Dewald traces this evolution through several key phases. Prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), only a handful of states used 1115 waivers to provide housing-related services, primarily focused on residential care for high-risk groups (e.g., skilled nursing facilities, group homes, and long-term care). The passage of the ACA in 2010 marked a turning point, as the Obama administration actively encouraged states to use waivers to address social determinants of health, including housing instability. 1115 waivers since 2010 have addressed food insecurity, post-incarceration re-entry programs, healthy behavior incentives, substance-use disorder, value-based payment programs and more!

The scope of these efforts expanded notably following the COVID-19 pandemic1. As of April 2024, 17 states have approved or pending 1115 waivers specifically targeting homelessness2. These programs vary in their approach, but most include tenancy support services to help individuals locate and maintain stable housing. More significantly, ten states have now received approval to cover direct housing costs like rent and utilities – marking the first time in Medicaid's history that such expenses have been deemed allowable.

The geographic distribution of these waiver programs is telling. States with the highest rates of homelessness are more likely to have waivers in place, with twelve of the seventeen programs located in states falling in the top two quartiles for homelessness rates3. The programs are also predominantly found in states that have expanded Medicaid under the ACA, with Florida being the only non-expansion state to implement such a waiver. This likely indicates a more active and innovative state Medicaid agency.

Recent guidance from CMS has further clarified and expanded the potential for these programs. Under the Biden administration's framework for addressing "Health-Related Social Needs," states can now use 1115 waivers to provide up to six months of housing costs for eligible populations, including individuals transitioning out of institutional settings or experiencing chronic homelessness. This must be paired with appropriate medical services and support to help individuals transition to long-term, non-Medicaid housing solutions.

Operational Challenges and Technology Platforms

Willison and Dewald indicate that these housing programs require a great deal of coordination and integration of overlapping services and community-based organizations. Thus, in recent years, software has become increasingly critical to operations.

For example, New York City's Street Health Outreach and Wellness (SHOW) program demonstrates how technology can enhance Medicaid waiver-supported homeless services in practice. The program utilizes a mobile application system that allows outreach workers to document encounters, assess needs, and coordinate care for individuals experiencing homelessness in real-time. Healthcare providers can access a secure portal that displays when their patients have been contacted by outreach teams, received services at mobile clinics, or expressed interest in housing placement. The system integrates with the city's Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) and local hospital electronic health records, creating a comprehensive view of an individual's interactions with both healthcare and housing services. For example, when a SHOW participant visits an emergency department, their care team receives an automatic notification and can coordinate appropriate follow-up care and housing support services.

Return on Investment Analyses

The delivery of these programs requires funding, and that funding is in limited supply, so it is critical that they generate true return on investment (ROI). That return on investment usually comes from the avoidance of future health care spending by the Medicaid program.

One study looking at housing-related program ROI across multiple programs found that the average ROI is 50%. Another review by the Commonwealth Fund contains a study that found ROIs of $2, 249 per patient per month and another that demonstrated $1.57 dollars saved for each dollar invested in the program. Of course, the specific design and target population of each program influences the outcome as does the cost of care in the areas where those patients were served.

Practically, if we want to operate more efficient government health programs and reduce the cost to taxpayers, then these types of investments make sense. If housing instability contributes or causes expensive health services utilization, then it makes sense to solve that problem even though Medicaid was originally designed to cover basic medical care needs.

Political Philosophy and the Role of Government

Medicaid and other government health programs created under the Social Security Act were conceptualized during a time when the capabilities of medical care were in an infancy. Today’s medical tool set is much expanded from the early days of the program. This expansion, in recent years, has also grown to include concepts outside of doctor’s visits, drugs, medical devices, and surgery. We are now asking medical professionals to screen and address social determinants of health due to their outsized impact on health outcomes and cost. If the goal of medical care is to mitigate the effects of disease on humans, then it makes logical sense to intervene in areas, like housing instability, that contribute to poor health.

However, this concept was not incorporated into the structures and benefit categories of the major federal health programs at the beginning. Waivers, like the Section 1115, allow for an expansion of benefits beyond the statutory benefit categories.

But, this begs a question as old as organized government. How far should the government reach to address basic human needs? How much support should the collective society provide for the poor? What kinds of support are supported politically?

A practical observer would likely look at the ROI calculations and suggest that it makes sense. An opponent might lean into the concepts of individual responsibility and government over reach. A supporter might suggest that an advanced society is marked by how well it treats its poor and less fortunate. An economist might suggest that the economic benefits to society outweigh the costs.

A great book, by Dr. Matt Desmond at Princeton University, Evicted, follows families through the challenges with housing instability and leads to the conclusion that those in these situations are locked in a cycle of poverty that is nearly impossible to break out of even given the will to do so. The concepts of individual responsibility within a society are often directly in conflict with systemic barriers in the United States to “pulling oneself up by the bootstraps.” This book demonstrates these issues very well.

Conclusions

While these Medicaid innovations show promise, important questions remain about their long-term impact and sustainability. The time-limited nature of housing support and the need to coordinate with existing housing systems present significant implementation challenges, however software platforms and patient engagement technologies can help make this easier. However, the bipartisan support these programs have received across three presidential administrations suggests they will likely continue to play an important role in addressing America's homelessness crisis.

As states gain more experience with these programs and evaluation data becomes increasingly available, we will better understand their effectiveness in both reducing homelessness and controlling healthcare costs. For now, they represent a creative attempt to leverage healthcare resources to address one of our most complex social challenges, demonstrating how policy innovation can help bridge the gap between healthcare and housing systems.

This evolution in Medicaid's role reflects a growing recognition that addressing homelessness requires more than traditional housing programs alone. This approach looks across government programs and identifies how investments by one siloed program can impact expenditures in another. This type of cross-government innovation offers an opportunity to build more effective and efficient programs. Software technologies and data science approaches can allow for these opportunities to be identified and better coordinated.

So, I will leave you with the following to ponder:

Medicaid spending by both states and the federal government was $880 Billion in 2023.

The HUD budget for homelessness and housing voucher programs in 2023 was $35.7 Billion.

HUD estimates $20B to end homelessness. Another analysis by Rob Moore suggests a range from $11B to $30B.

Let’s assume that the program mirrors that of the most effective 1115 waivers and lets discount the ROI number from $1.5 to $1.2 per dollar spent on the program due to inefficiencies and certain populations not responding like those in the studies.

An investment of $20B could yield $24B in savings in health care cost avoidance alone4. There are other areas where this policy might save additional funds including for city governments, hospitals, and other federally-funded programs.

Charley E. Willison, Alisa Dewald; Medicaid Waivers to Address Homelessness: Political Development and Policy Trajectories. J Health Polit Policy Law 2024; 11670160. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-11670160

Ibid. 1.

Ibid. 1.

This is a very simple analysis and the reality is likely much different than this, but the point of this is to present an interesting thought experiment.